We’ll sit down at our feasts tomorrow inspired by the First Thanksgiving in 1621.

The Pilgrims landed in November of 1620. Half died of disease and starvation before the famous harvest of 1621. They were likely joined by  the Native American tribe, the Wampanoag. This tribe had been infected by the bacteria, leptospirosis when European ships had visited in 1616. This disease, thought at various times to be typhus or small pox, killed 90% of the Wampanoag people by 1619. A microbe. Invisible to the human eye. The most horrible, horriblest-ever human invader would stare in amazement at such a death rate.

the Native American tribe, the Wampanoag. This tribe had been infected by the bacteria, leptospirosis when European ships had visited in 1616. This disease, thought at various times to be typhus or small pox, killed 90% of the Wampanoag people by 1619. A microbe. Invisible to the human eye. The most horrible, horriblest-ever human invader would stare in amazement at such a death rate.

These grieving people gave thanks and, no matter how much controversy swirls among historians of the “real” truth of the event, we should hold the idea of peace between diverse peoples and thanks born of suffering as sacred. Worth remembering and celebrating after hundreds of years.

My personal thanksgiving goes out to the Native American who planted my 300 year old tree mott. The huge Live Oak has an Elm tree in its center. I understand that the Native Americans planted these trees together. It is horticultural genius, since the shallow roots of the Live Oak are held in place by the deep roots of the Elm, and the tall and brittle trunk of the Elm is protected from our sometimes ferocious winds by the Oak. After a storm, giant Live Oaks will be lying on the ground throughout my neighborhood, their roots exposed; and not 50 feet from my front door a 60-foot Elm (not protected by its own Oak) cracked in half last year during a terrible spring wind.

Back in the 1800’s a the Comanche and Tonkawa tribes lived near my home.

The Comanches had come tearing down from the Pacific Northwest, drove most of the Apaches out of the Southwest and were putting pressure from the west on the Tonkawa by the 1800’s. The Tonkawa, called the “original people of Texas”, were pressured at the same time from the east by the white settlers. But some skilled horticulturist from one of these tribes likely planted my combination tree.

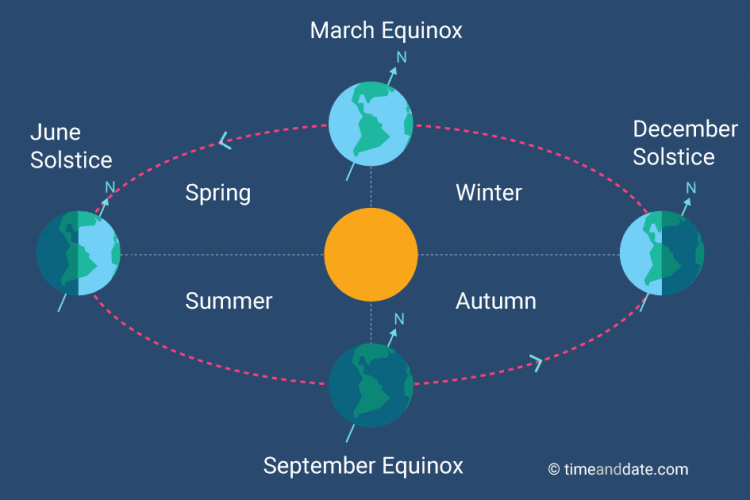

Of course, hunting and meat eating were important to the Native Americans, but both the Comanches and the Tonkawa commonly ate corn; roots like potatoes, prairie turnips and onions; vegetables such as spinach; and also wild berries and fruits. Colin Tudge and other scientists believe that agriculture began after the last Ice Age. Neanderthals, Bandits and Farmers: How Agriculture Really Began, Tudge.

That is another post. In any case, it is not only the horticultural expertise of the Native American who planted my tree mott that I admire. I am amazed, humbled at his or her long view. This person was creating shade, not for his or her generation, but for generations a hundred and more years away. Oak and Elm are slow growers, planted for great grandchildren. The tree mott may have been 10 feet tall in by the late 1800’s when the American army ‘relocated’ the Comanches and Tonkawans to Oklahoma. Now it’s 50+ feet tall and my grasses, microbes, chickens, sheep, and I seek the shade of this tree on hot days. And we give thanks.

ground. They can sprint up to 30 miles an hour and swim two miles of open ocean. The males develop muscles in the front of their bodies that thicken like armor and are almost impermeable. Their noses have a special bone, the nasal sesamoid bone, which is connected to the skull only by cartilage and which provides extra rooting support. Some have tusks but these are often lost in fights between males.

ground. They can sprint up to 30 miles an hour and swim two miles of open ocean. The males develop muscles in the front of their bodies that thicken like armor and are almost impermeable. Their noses have a special bone, the nasal sesamoid bone, which is connected to the skull only by cartilage and which provides extra rooting support. Some have tusks but these are often lost in fights between males. Their destruction leaves wildlife bereft of food sources; and, they eat foxes, opossums, deer and other wildlife. The wild pigs contributed to the near-extinction of foxes on Santa Cruz Island off the coast of California.

Their destruction leaves wildlife bereft of food sources; and, they eat foxes, opossums, deer and other wildlife. The wild pigs contributed to the near-extinction of foxes on Santa Cruz Island off the coast of California.

hundreds of years. Of course, large enterprises use tractors and other mechanized vehicles. But with only a few animals, one just grabs an armful of hay and gets the job done.

hundreds of years. Of course, large enterprises use tractors and other mechanized vehicles. But with only a few animals, one just grabs an armful of hay and gets the job done.

Pyrenees, who acts like a big baby half the time, would not let me touch him; his feet and the outside of his mouth were covered with quills. He growled at me when I approached him with the leash. Unheard of! On the left is one of the dozens of photos of quills in dogs’ mouths on the internet, and this one is by no means the worst. I didn’t think to take a photo of my dogs since I was hurriedly loading them up for a trip to the vet. I had to lure the Pyr into the truck with hamburger. They were anesthetized and given pain medication and antibiotics and are now fine. Two dog owners appeared just after me with dogs bristling with quills; the vet said a couple of days later that they had been swamped with dogs who had been in battle with porcupines.

Pyrenees, who acts like a big baby half the time, would not let me touch him; his feet and the outside of his mouth were covered with quills. He growled at me when I approached him with the leash. Unheard of! On the left is one of the dozens of photos of quills in dogs’ mouths on the internet, and this one is by no means the worst. I didn’t think to take a photo of my dogs since I was hurriedly loading them up for a trip to the vet. I had to lure the Pyr into the truck with hamburger. They were anesthetized and given pain medication and antibiotics and are now fine. Two dog owners appeared just after me with dogs bristling with quills; the vet said a couple of days later that they had been swamped with dogs who had been in battle with porcupines. herbivores; none would dream of eating a chicken or lamb or small calf. There is no competition between them and predators. The savvy coyote is said to ignore them; big cats like leopards attack them. So do dogs. The porcupine signs its death sentence when it provokes a predator; it raises its quills and furiously waves its spiky tail from side to side and up and down, beating the ground. Its aggression sadly inflames the aggression of a large, strong animal with big teeth.

herbivores; none would dream of eating a chicken or lamb or small calf. There is no competition between them and predators. The savvy coyote is said to ignore them; big cats like leopards attack them. So do dogs. The porcupine signs its death sentence when it provokes a predator; it raises its quills and furiously waves its spiky tail from side to side and up and down, beating the ground. Its aggression sadly inflames the aggression of a large, strong animal with big teeth. Underneath their friendly ways, dogs are proud creatures, territorial at heart and many, like my guardian dogs, are bred to protect–to do their duty. Some are protective of their humans; mine protect chickens and livestock. My dogs embrace their guard duties. But in a tangle with a 20-pound porcupine, a predator’s injuries are often fatal. The quills are constructed to burrow deeper into flesh as time goes by.

Underneath their friendly ways, dogs are proud creatures, territorial at heart and many, like my guardian dogs, are bred to protect–to do their duty. Some are protective of their humans; mine protect chickens and livestock. My dogs embrace their guard duties. But in a tangle with a 20-pound porcupine, a predator’s injuries are often fatal. The quills are constructed to burrow deeper into flesh as time goes by. Untreated, infection sets in, then certain death. Neither the fearsome pit bull or the beautiful sports dog pictured here can survive the quills without help.

Untreated, infection sets in, then certain death. Neither the fearsome pit bull or the beautiful sports dog pictured here can survive the quills without help.

The different colors of the hives are to help the foraging bees easily find their home base. I enjoy linking my life to bee and honey lovers of ancient China, Babylonia, Crete and Israel. Sealed honey jars were found in the tomb of Tutankhamunin. Aristotle wrote lovingly of beekeeping as

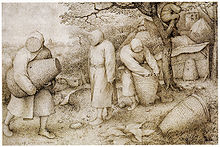

The different colors of the hives are to help the foraging bees easily find their home base. I enjoy linking my life to bee and honey lovers of ancient China, Babylonia, Crete and Israel. Sealed honey jars were found in the tomb of Tutankhamunin. Aristotle wrote lovingly of beekeeping as did a variety of Romans including Virgil and Gaius. Pictured left is an 8000-year old cave painting of a woman harvesting honey in Spain.

did a variety of Romans including Virgil and Gaius. Pictured left is an 8000-year old cave painting of a woman harvesting honey in Spain.  She’s doing her work without bee ‘gear’ unlike the 16th century Europeans on the right, who are wearing some crazy face protection.

She’s doing her work without bee ‘gear’ unlike the 16th century Europeans on the right, who are wearing some crazy face protection. ut that in December of last year.

ut that in December of last year.

There seems to be much fear of the 10,000-year dogma about the beginning of agriculture. They seem to belabor their case that the Ohalo people had knowledge of agriculture and had foresight – so that they could practice ‘agricultural planning’.

There seems to be much fear of the 10,000-year dogma about the beginning of agriculture. They seem to belabor their case that the Ohalo people had knowledge of agriculture and had foresight – so that they could practice ‘agricultural planning’.

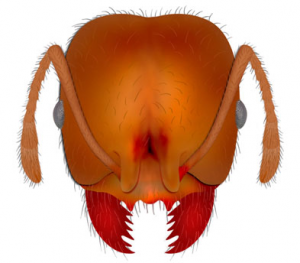

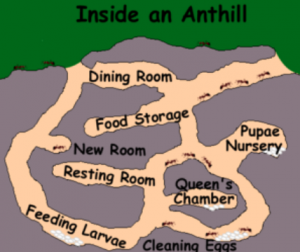

When I walk or stand near their nest, many of them will crawl onto my foot and, then get on their little IPhones and all bite me at the same time. Actually, I have recently learned that they do not communicate through electronics; they communicate through chemistry.

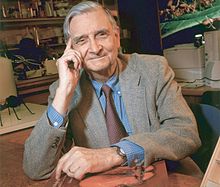

When I walk or stand near their nest, many of them will crawl onto my foot and, then get on their little IPhones and all bite me at the same time. Actually, I have recently learned that they do not communicate through electronics; they communicate through chemistry. But he enlisted two scientist friends and they traveled to Jacksonville where fire ants live in huge mounds. They shoveled the ants into large containers to take back to the lab. Wilson quips that his helpers were glad to get out of the field and back to the lab since the ants did not suffer being shoveled lightly and covered the scientists with painful bites that form itchy white pustules within a few days.

But he enlisted two scientist friends and they traveled to Jacksonville where fire ants live in huge mounds. They shoveled the ants into large containers to take back to the lab. Wilson quips that his helpers were glad to get out of the field and back to the lab since the ants did not suffer being shoveled lightly and covered the scientists with painful bites that form itchy white pustules within a few days. “When an ant is squashed it releases a different pheromone that warns the others of potential danger. Pheromones also help ants to distinguish between different family members, nest mates and strangers.” There are dozens of known meanings to these pheromome communications and likely more to come.

“When an ant is squashed it releases a different pheromone that warns the others of potential danger. Pheromones also help ants to distinguish between different family members, nest mates and strangers.” There are dozens of known meanings to these pheromome communications and likely more to come.