Plantswoman is taking a break for the balance of the year. In January, I will publish on the first Wednesday of every month during the year 2019. The following post was from November 2016.

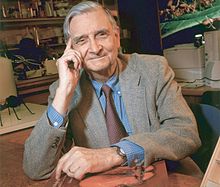

“When you thrust a shovel into the soil or tear off a piece of coral, you are, godlike, cutting through an entire world.” Edward O. Wilson

Good soil is alive, a small pail of soil has more microscopic organisms than there are people on earth. http://www.sustainable-gardening.com/inputs-tools/soil-fertilizers/great-soil For the gardener the most magical of these tiny organisms is mycelium—fungus.

Fungal mycellium is a web. It is called “the neurological network of nature”. It is believed that behaves like a “sentient membrane” channeling information about nutrients and disease across a garden, across a prairie, across miles of forestland. Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World by Paul Stamets. I’ll say it again and again, it is clear humans do not have a corner on the sentience market. Stamets’ book is a rocking good read, and in addition to his theories on the communication skills of underground mycellium, the book contains a thorough description of the many forms of fungus that appear above ground: mushrooms, the poisonous, the hallucinogenic, the edible.

Fungal mycellium is a web. It is called “the neurological network of nature”. It is believed that behaves like a “sentient membrane” channeling information about nutrients and disease across a garden, across a prairie, across miles of forestland. Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World by Paul Stamets. I’ll say it again and again, it is clear humans do not have a corner on the sentience market. Stamets’ book is a rocking good read, and in addition to his theories on the communication skills of underground mycellium, the book contains a thorough description of the many forms of fungus that appear above ground: mushrooms, the poisonous, the hallucinogenic, the edible.

Two things are necessary to encourage mycellium in the garden where it protects plants from disease and helps them take up nutrients. The first is a practice of no-till gardening, the second is adding as much organic matter to the garden as you can get your hands on.

No-till gardening is far from an accepted practice. I am pretty sure that the spade, the rototiller, the plow break up the mycelium networks that protect and nourish plants. Edward H. Faulkner shocked the farm and garden world in his 1943 book, Plowman’s Folly, arguing, in his charming –sort of grumpy — writing style, that “no one has ever advanced a scientific reason for plowing.”

It seems logical that friable, loose earth would allow roots to spread evenly and to proliferate, and short term, this is indeed the case. But in the long term, tillage has a disastrous effect on fungi as it physically breaks up the mycelium network. http://www.soilquality.org.au/factsheets/soil-bacteria-and-fungi-nsw

I have dutifully planted my garden to avoid disturbing the mycelium. But gardening is not all smooth sailing. I recently planted garlic in a 4×8 foot raised bed making small holes for each clove. My guardian dogs, given access to the garden for the benefits of their predator scent, have now converted this little area to a kind of dog lounge with their big paws, digging as deep as a foot within the cedar planks that surround the “garden” bed.  I explained to the dogs that they had torn up my mycelium that helps decompose organic matter; that the mycelium improves soil structure and has a symbiotic relationship with plant roots, called mycorrhizae. I went on to tell them that many kinds of plants require mycorrhizae in order to absorb the nutrients they need for healthy growth. These relationships between fungi and plant roots have developed over MILLIONS of years. The dogs were indifferent to all this science and very proud of their new doggie lounge. Setbacks aside (the dear dogs are up all night these days driving away foxes, coyotes, cats, raccoons, skunks and heaven knows what else; all born in the spring and present now in my little canyon in great numbers), it is the time of year to add organic matter to the garden so it can decompose over the winter.

I explained to the dogs that they had torn up my mycelium that helps decompose organic matter; that the mycelium improves soil structure and has a symbiotic relationship with plant roots, called mycorrhizae. I went on to tell them that many kinds of plants require mycorrhizae in order to absorb the nutrients they need for healthy growth. These relationships between fungi and plant roots have developed over MILLIONS of years. The dogs were indifferent to all this science and very proud of their new doggie lounge. Setbacks aside (the dear dogs are up all night these days driving away foxes, coyotes, cats, raccoons, skunks and heaven knows what else; all born in the spring and present now in my little canyon in great numbers), it is the time of year to add organic matter to the garden so it can decompose over the winter.

This can also be called ‘making compost’. I layer the summer waste: melon vines, tomato greenery and grapevine leaves with manure, hay and soil from the stock pen. This creates a little mound about 2 feet tall and 3 feet across. Next September, I’ll rake it out and have a lovely planting space for my winter garden. Composting always sounds complicated, huge piles, turned by a tractor, measured by a giant thermometer. Or it is expensive when purchased at soil suppliers or nurseries. But it can just be making a layer cake of what’s on hand and being patient. The mycelium love my little garden layer cakes of organic materials. I can tell since small mushrooms tell me so by sprouting up all over the place.

Pounded by heavy rain, the soil spreads out and its structure fails. Nutrients are leached away, including vitamins, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulfur.

Pounded by heavy rain, the soil spreads out and its structure fails. Nutrients are leached away, including vitamins, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulfur.  Degraded pastures are a common sight here, many uncared for because, among other things, owners expect the land to be developed for new housing. And when heavy rain hits empty fields of rocky degraded soil, it runs off and the result is flooding. Too much rain is a common story.

Degraded pastures are a common sight here, many uncared for because, among other things, owners expect the land to be developed for new housing. And when heavy rain hits empty fields of rocky degraded soil, it runs off and the result is flooding. Too much rain is a common story.

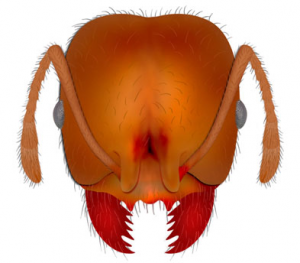

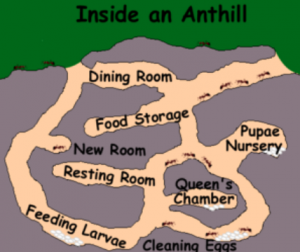

When I walk or stand near their nest, many of them will crawl onto my foot and, then get on their little IPhones and all bite me at the same time. Actually, I have recently learned that they do not communicate through electronics; they communicate through chemistry.

When I walk or stand near their nest, many of them will crawl onto my foot and, then get on their little IPhones and all bite me at the same time. Actually, I have recently learned that they do not communicate through electronics; they communicate through chemistry. But he enlisted two scientist friends and they traveled to Jacksonville where fire ants live in huge mounds. They shoveled the ants into large containers to take back to the lab. Wilson quips that his helpers were glad to get out of the field and back to the lab since the ants did not suffer being shoveled lightly and covered the scientists with painful bites that form itchy white pustules within a few days.

But he enlisted two scientist friends and they traveled to Jacksonville where fire ants live in huge mounds. They shoveled the ants into large containers to take back to the lab. Wilson quips that his helpers were glad to get out of the field and back to the lab since the ants did not suffer being shoveled lightly and covered the scientists with painful bites that form itchy white pustules within a few days. “When an ant is squashed it releases a different pheromone that warns the others of potential danger. Pheromones also help ants to distinguish between different family members, nest mates and strangers.” There are dozens of known meanings to these pheromome communications and likely more to come.

“When an ant is squashed it releases a different pheromone that warns the others of potential danger. Pheromones also help ants to distinguish between different family members, nest mates and strangers.” There are dozens of known meanings to these pheromome communications and likely more to come.

avor of spiders, especially literate ones who write in spun silk and save pigs. Anyone who hates spiders should read this book; it might take a couple of hours, but they would be saved from a form of human silliness. Spiders eat roaches, earwigs, flies, moths and mosquitoes. And aphids. Also fleas; fleas that have spread typhus and the bubonic plague. They are beneficials. Not that rational thought informs our prejudices: bubonic plague or no, in European literature, spiders have not fared well. For example, spiders eat Hobbits. Well, the giant spider Shelob tried to do so. But since Sam killed Shelob, that spider problem is quite dead.

avor of spiders, especially literate ones who write in spun silk and save pigs. Anyone who hates spiders should read this book; it might take a couple of hours, but they would be saved from a form of human silliness. Spiders eat roaches, earwigs, flies, moths and mosquitoes. And aphids. Also fleas; fleas that have spread typhus and the bubonic plague. They are beneficials. Not that rational thought informs our prejudices: bubonic plague or no, in European literature, spiders have not fared well. For example, spiders eat Hobbits. Well, the giant spider Shelob tried to do so. But since Sam killed Shelob, that spider problem is quite dead.

pe with dozens of bees at a feeder and simply give up since the hungry and thirsty bees were relentless. Other insects also compete for the sugar water: moths, hornets, spiders, praying mantises, and earwigs.

pe with dozens of bees at a feeder and simply give up since the hungry and thirsty bees were relentless. Other insects also compete for the sugar water: moths, hornets, spiders, praying mantises, and earwigs. he bottom of the iron stake where my feeder hangs with cling wrap and paint on the Tanglefoot that forms a barrier to ant invasions. Of course the wretched ants number in the millions so the Tanglefoot has to be reapplied once a week. There are also ant traps that hang above the feeder. Filled with plain water, these act as a moat that forces ants to face drowning to get to the sugar water.

he bottom of the iron stake where my feeder hangs with cling wrap and paint on the Tanglefoot that forms a barrier to ant invasions. Of course the wretched ants number in the millions so the Tanglefoot has to be reapplied once a week. There are also ant traps that hang above the feeder. Filled with plain water, these act as a moat that forces ants to face drowning to get to the sugar water.

illiance to us. I would love to think, the Dahlia, for example, would use it’s nematode destroying abilities to assist me in my endless struggle to grow nematode-free potatoes. But I imagine the Dahlia is serving its own interests as are all other flowers; if they had any thought for my human well being, they would certainly do something about the wretched fire ants for me.

illiance to us. I would love to think, the Dahlia, for example, would use it’s nematode destroying abilities to assist me in my endless struggle to grow nematode-free potatoes. But I imagine the Dahlia is serving its own interests as are all other flowers; if they had any thought for my human well being, they would certainly do something about the wretched fire ants for me. Another family of plants from Asia, considered to be a broad-spectrum natural insecticide, is the Allium.

Another family of plants from Asia, considered to be a broad-spectrum natural insecticide, is the Allium.  wild.

wild.