The terrible decline of bees is a frequent topic here, but today I’ll set aside my usual complaints about the 40% losses of the bee population due to pollution, paving and the overuse of pesticides by humans. Bees are a part of the natural world; the world of nature which includes a give and take with other beings who need food. Bees, like the majority of Earth’s creatures suffer during the winter; and, food pressures during late winter and early spring are the most intense.

When food is scarce, skunks, woodpeckers, badgers, raccoons, mice and opossums will prey on bees.The bees themselves are nutritious, the spring brood is loaded with protein and the honey is a wonderful winter treat. When the ground is frozen, a woodpecker will drill a hole in the bee box to get at the bees and honey. Some predators like the badger or the fox will knock over the bee hive and feast. Skunks and raccoons will scratch on the hive and as bees emerge to defend the hive, they eat the bees. There are toads and frogs that sit on the hive entrance and eat bees as they leave the hive.

When food is scarce, skunks, woodpeckers, badgers, raccoons, mice and opossums will prey on bees.The bees themselves are nutritious, the spring brood is loaded with protein and the honey is a wonderful winter treat. When the ground is frozen, a woodpecker will drill a hole in the bee box to get at the bees and honey. Some predators like the badger or the fox will knock over the bee hive and feast. Skunks and raccoons will scratch on the hive and as bees emerge to defend the hive, they eat the bees. There are toads and frogs that sit on the hive entrance and eat bees as they leave the hive.  Beekeepers will strap hives closed and some use electric fencing; my dogs protect my hives from these predators.

Beekeepers will strap hives closed and some use electric fencing; my dogs protect my hives from these predators.

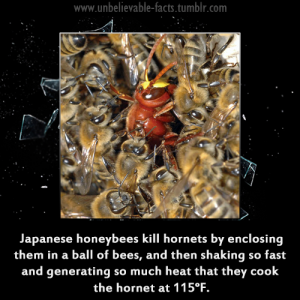

Other insects eat bees too. Wasps are very thorough and can wipe out a hive in a few days. They eat the honey, the brood and the bees. link Yellow jackets, mites, spiders all like a bee for dinner. Of course, the bees defend the nest. My africanized bees have defended themselves from the dreaded Varona mite, and from wasps so far.

When winter begins, bees will have stored up as much h oney as possible to make it through the winter. When the cold hits, the workers envelope the queen in what is called cluster. The bees then “shiver” moving their wings rapidly. This warms the hive. The temperature range in the hive can be as low as the 40’s near the exterior to a high, typically of 80 degrees, at the center of the cluster. To expend all this energy the bees must have plenty of honey. If they run out of honey the hive dies.

oney as possible to make it through the winter. When the cold hits, the workers envelope the queen in what is called cluster. The bees then “shiver” moving their wings rapidly. This warms the hive. The temperature range in the hive can be as low as the 40’s near the exterior to a high, typically of 80 degrees, at the center of the cluster. To expend all this energy the bees must have plenty of honey. If they run out of honey the hive dies.

Winter losses of bees average 10 to 15% and bad conditions can cause a beekeeper losses of closer to 100%. For example, in a year of drought, it’s hard for bees to store enough honey to last a winter. My beekeeper came last Sunday to check my hives and she said my bees had plenty of honey to last the res t of winter. She had inspected hives that were in trouble and that would need sugar supplements to make it through. I was thrilled of course and glad the MacMillan Sunflowers and the White Wood Asters had done so well last fall. Both plants are covered with bees for weeks.

t of winter. She had inspected hives that were in trouble and that would need sugar supplements to make it through. I was thrilled of course and glad the MacMillan Sunflowers and the White Wood Asters had done so well last fall. Both plants are covered with bees for weeks.

The little drones were equipped with gel stuck onto horse hair. An electrical charge kept pollen grains attached during flight. Could this be a solution to the potential extinction of bees?

The little drones were equipped with gel stuck onto horse hair. An electrical charge kept pollen grains attached during flight. Could this be a solution to the potential extinction of bees? could the little robo-drones communicate? Bees can. Among other communication skills, a scout will return to the hive and perform a little dance that illustrates to other bees the direction of a discovered food source and its distance from the hive.

could the little robo-drones communicate? Bees can. Among other communication skills, a scout will return to the hive and perform a little dance that illustrates to other bees the direction of a discovered food source and its distance from the hive. One research team “found that antenna deflections induced by an electrically charged honey bee wing are about 10 times the size of those that would be caused by airflow from the wing fluttering at the same distance—a sign that electrical fields could be an important signal.”

One research team “found that antenna deflections induced by an electrically charged honey bee wing are about 10 times the size of those that would be caused by airflow from the wing fluttering at the same distance—a sign that electrical fields could be an important signal.”

One such critic welcomes a population decline. The aserbic and controversial John Zerzan, an anarchist and primitivist philosopher, is a hater not only of agriculture, but all technology. It is hard to disagree with Zerzan and other anti-agriculturists since where agriculture has been practiced, intensely lush and beautiful land has turned into rocky, dry terrain.

One such critic welcomes a population decline. The aserbic and controversial John Zerzan, an anarchist and primitivist philosopher, is a hater not only of agriculture, but all technology. It is hard to disagree with Zerzan and other anti-agriculturists since where agriculture has been practiced, intensely lush and beautiful land has turned into rocky, dry terrain.  d become a desert of sand and gravel, alternately wet and dry, always fruitless. It was even more worthless than the hills. Its sole harvest now is dust, picked up by the bitter winds of winter that rip across its dry surface in this land of rainy summers and dry winters.”

d become a desert of sand and gravel, alternately wet and dry, always fruitless. It was even more worthless than the hills. Its sole harvest now is dust, picked up by the bitter winds of winter that rip across its dry surface in this land of rainy summers and dry winters.”

grams that value chemical growing processes, ease of shipping and long shelf life over taste, the one that resonates with me is the story of bread. The puffy over-processed white stuff in our stores will last forever. It is making some people sick and others suffer blood sugar issues when they eat it.

grams that value chemical growing processes, ease of shipping and long shelf life over taste, the one that resonates with me is the story of bread. The puffy over-processed white stuff in our stores will last forever. It is making some people sick and others suffer blood sugar issues when they eat it. rrot’, which he serves in his high end restaurant as a ‘steak’. The carrot dominates the plate. He can do this only because the carrot is delicious; it is a carrot with a long heritage grown in really good soil. “Taste doesn’t come from the elemental compounds. It comes from the synthesis… Phytonutrients— like amino acids, esters, and flavonoids— are key to the flavor of the mokum carrot,”

rrot’, which he serves in his high end restaurant as a ‘steak’. The carrot dominates the plate. He can do this only because the carrot is delicious; it is a carrot with a long heritage grown in really good soil. “Taste doesn’t come from the elemental compounds. It comes from the synthesis… Phytonutrients— like amino acids, esters, and flavonoids— are key to the flavor of the mokum carrot,”

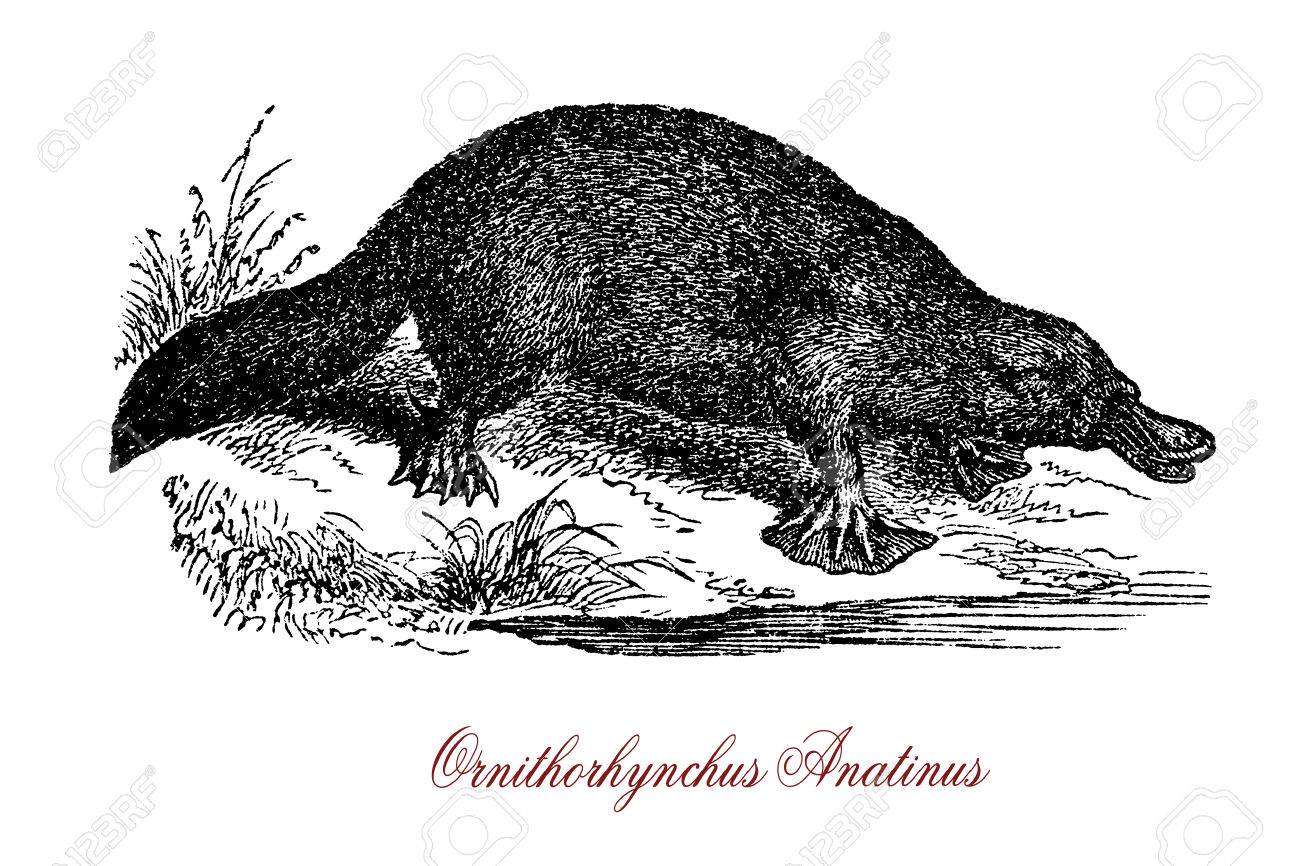

Is it a mammal or a reptile or a bird? The remarkable platypus has a thick, beautiful coat of fur and looks at first glance like any respectable mammal. But the mother platypus digs a burrow on a river bank where she lays her eggs. After hatch, unique from all other animals, she nurses her babies with breast milk. In addition, this amazing animal has what appears to be a duckbill, but a very fancy one fitted out with exquisitely sensitive nerve endings called electroreceptors that detect prey. Its reptilian sideways feet scream alligator; the male platypus has a stinger with venom, like a snake, that can sentence a victim to months of pain unaffected by opiates.

Is it a mammal or a reptile or a bird? The remarkable platypus has a thick, beautiful coat of fur and looks at first glance like any respectable mammal. But the mother platypus digs a burrow on a river bank where she lays her eggs. After hatch, unique from all other animals, she nurses her babies with breast milk. In addition, this amazing animal has what appears to be a duckbill, but a very fancy one fitted out with exquisitely sensitive nerve endings called electroreceptors that detect prey. Its reptilian sideways feet scream alligator; the male platypus has a stinger with venom, like a snake, that can sentence a victim to months of pain unaffected by opiates. tells us the platypus was ‘discovered’ in Australia in 1797. I imagine Platypuses were perfectly aware of their existence long before European naturalists first spotted them swimming happily in a river just outside Sydney. The platypus was a contemporary of dinosaurs according to Timothy Rowe of the University of Texas, surviving “without any problem” the 85% extinction of life, including all the dinosaurs, at the end of the Cretaceous.

tells us the platypus was ‘discovered’ in Australia in 1797. I imagine Platypuses were perfectly aware of their existence long before European naturalists first spotted them swimming happily in a river just outside Sydney. The platypus was a contemporary of dinosaurs according to Timothy Rowe of the University of Texas, surviving “without any problem” the 85% extinction of life, including all the dinosaurs, at the end of the Cretaceous.

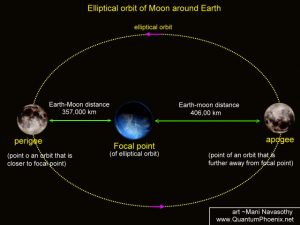

Of course the Moon can roll by in Perigee when it is new or waxing or waning–or, when it is full. It seems very grand that the Moon was full the very day we set out on the new road of the year, 2018. January 1, 2018 was special since the Moon was not only full but close, very close. It visited us at what is called “extreme perigee distance”–only 221,559 miles away. The Moon won’t be this close to us again until November 25, 2034. The closest full moon of the 21st century will fall on December 6, 2052–so mark your calendars!

Of course the Moon can roll by in Perigee when it is new or waxing or waning–or, when it is full. It seems very grand that the Moon was full the very day we set out on the new road of the year, 2018. January 1, 2018 was special since the Moon was not only full but close, very close. It visited us at what is called “extreme perigee distance”–only 221,559 miles away. The Moon won’t be this close to us again until November 25, 2034. The closest full moon of the 21st century will fall on December 6, 2052–so mark your calendars!  moon at perigee. Some scientists, skywatchers and news media say the difference between a full moon at perigee and one at apogee is not perceptible to the naked eye. Others tout the extra 30 % of brightness and the 14% difference in size.

moon at perigee. Some scientists, skywatchers and news media say the difference between a full moon at perigee and one at apogee is not perceptible to the naked eye. Others tout the extra 30 % of brightness and the 14% difference in size. don’t help us really “see” our Moon. We have to look at it first hand. And what we see is cold and bright with no hint of the Moon’s history of fire and violence described and illustrated by Ron Miller several years ago.

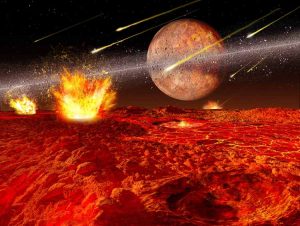

don’t help us really “see” our Moon. We have to look at it first hand. And what we see is cold and bright with no hint of the Moon’s history of fire and violence described and illustrated by Ron Miller several years ago.  I love the illustrations here showing the turmoil. The illustration at the top of the page shows the current quiet, stark surface of a Moon that roiled with fire in the past. But no more.

I love the illustrations here showing the turmoil. The illustration at the top of the page shows the current quiet, stark surface of a Moon that roiled with fire in the past. But no more.

They learn to avoid traps. If one pig from a sounder escapes, no other pig will ever go near that trap again. New traps are monitored electronically and programed to close only when every member of the sounder is in the trap. The other issue with trapping is that a pig or pigs confined in a trap are going to be extremely dangerous. A study done in South Carolina found that catching and harvesting wild hogs in traps required about twenty-nine man-hours per hog.

They learn to avoid traps. If one pig from a sounder escapes, no other pig will ever go near that trap again. New traps are monitored electronically and programed to close only when every member of the sounder is in the trap. The other issue with trapping is that a pig or pigs confined in a trap are going to be extremely dangerous. A study done in South Carolina found that catching and harvesting wild hogs in traps required about twenty-nine man-hours per hog. hat bay when the pig is found; and “catch dogs” that hold the pig by the ear or nose while the hunters come in for the kill. These hunters travel with surgical stapling guns, suture kits, and blood-stop powder and very valuable dogs are outfitted with vests made of ballistic-strength fiber.

hat bay when the pig is found; and “catch dogs” that hold the pig by the ear or nose while the hunters come in for the kill. These hunters travel with surgical stapling guns, suture kits, and blood-stop powder and very valuable dogs are outfitted with vests made of ballistic-strength fiber.