I enjoyed a happy childhood; my mother was considered a good cook and family meals were a pleasure most of the time–although not without drama on occasion. Herbs were entirely unknown to us. We always had a salad or a vegetable–home grown at times, but we did not eat herbs. No one I knew ate herbs.

It’s not as though humans had not run across herbs yet. In Genesis, we read that every “herb bearing seed” was gifted to humankind. Pliny the Elder praises mint for its marvelous smell and taste. He wrote about the herb 2000 years ago. Hamlet speaks of fennel and rue and violets. We drank gallons of iced tea without fresh mint to flavor it. Why we didn’t include fennel and violets in our salads I’ll never know.

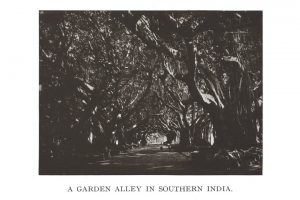

My favorite garden plants may be my herbs. I decided I had to grow them when I began reading about English cottage gardens, one of which is pictured above. Herbs and flowers and vegetables were just tucked in here and there without a grand plan. Many cottage garden plants self seed and skill is required to let the plants have their way when they pick some corner of the garden.

I am pretty sure basil did not grace my garden last summer because I was too enthusiastic w ith the hoe. It had popped up all over the garden for years, a tropical plant that loves hot summer days and hates the cold. It is native to Africa and Southeast Asia but is grown and used by cooks all over the world. Of course such a well-traveled plant has many names, basil being derived from Latin meaning kingly plant. It is like a king in the kitchen with it strong taste and scent; my son makes pesto each year, I love it raw or cooked, in salads, on bruschetta, any way at all. And there are dozens of kinds of basil: sweet basil, cinnamon basil, purple basil, anise or Persian basil, all worth growing.

ith the hoe. It had popped up all over the garden for years, a tropical plant that loves hot summer days and hates the cold. It is native to Africa and Southeast Asia but is grown and used by cooks all over the world. Of course such a well-traveled plant has many names, basil being derived from Latin meaning kingly plant. It is like a king in the kitchen with it strong taste and scent; my son makes pesto each year, I love it raw or cooked, in salads, on bruschetta, any way at all. And there are dozens of kinds of basil: sweet basil, cinnamon basil, purple basil, anise or Persian basil, all worth growing.

An herb that does not mind the cold is parsley. It is a biennial and flowers every other year, then the seeds scatter across the garden and come up where they please. I had a lar ge plant in the middle of the path last year. This year it is thriving at the feet of a grapevine. When temperatures dropped to 13 degrees in the winter I put a bucket over the plant and it was unharmed. Its leaves are very welcome in the kitchen during the cold weather. Parsley doesn’t mind hot summer weather either. I have found it to be delicious in salsa. The combination of tomatoes, onion, peppers and cilantro is grand; but cilantro likes it cool and is often gone by the time the tomatoes and peppers are ripe.

ge plant in the middle of the path last year. This year it is thriving at the feet of a grapevine. When temperatures dropped to 13 degrees in the winter I put a bucket over the plant and it was unharmed. Its leaves are very welcome in the kitchen during the cold weather. Parsley doesn’t mind hot summer weather either. I have found it to be delicious in salsa. The combination of tomatoes, onion, peppers and cilantro is grand; but cilantro likes it cool and is often gone by the time the tomatoes and peppers are ripe.

Cilantro also wanders all over the garden. It was by the holly last year. Cilantro is the Spanish name for the plant, coriander another name, although coriander is normally used for the seeds that form as soon as the weather heats up. The plant is native to Iran, but, like all beloved cooking herbs, it has been spread all over the world. Seed pods of the herb, called mericarps, were found in a Neolithic cave in Israel and over two cups were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb.

I will have to say that I love my thyme since it stays put. It forms a sort of homely little bush; it loves heat and doesn’t mind the cold. Mine has reliably come back year after year.  A friend whose thyme had spread too much brought me a beautiful clump several weeks ago and it is doing well. I would like this plant to cover as much of the garden as it likes, to go out of control. This herb also has a venerable past: it was used for embalming by the Egyptians, as incense by the the Greeks, used to flavor cheese by the Romans and used to cover bad smells by medieval Europeans. It’s loaded with health benefits. Bees love its flowers. Fungus doesn’t like it; bugs don’t bother it. Did I say I love this plant?

A friend whose thyme had spread too much brought me a beautiful clump several weeks ago and it is doing well. I would like this plant to cover as much of the garden as it likes, to go out of control. This herb also has a venerable past: it was used for embalming by the Egyptians, as incense by the the Greeks, used to flavor cheese by the Romans and used to cover bad smells by medieval Europeans. It’s loaded with health benefits. Bees love its flowers. Fungus doesn’t like it; bugs don’t bother it. Did I say I love this plant?

A distant relative of thyme and a member of the mint family, oregano, is also a perennial.  It grows into a large clump and its flowers are beautiful. High-end chefs use the flowers in their expensive dishes. It is reportedly hard to get an oregano plant that has ‘real’ oregano flavor. I may order Greek oregano and Syrian oregano this year from a reliable herb nursery. I understand that really strong oregano can numb the tongue. And the herb is the only one I know of that is reportedly better when dried. I will hang on to my trusty old oregano that has thrived in my hot, alkaline soil for years, it is beautiful in and out of bloom. I have been too lazy to dry it, but a big handful picked fresh is always welcome in my kitchen.

It grows into a large clump and its flowers are beautiful. High-end chefs use the flowers in their expensive dishes. It is reportedly hard to get an oregano plant that has ‘real’ oregano flavor. I may order Greek oregano and Syrian oregano this year from a reliable herb nursery. I understand that really strong oregano can numb the tongue. And the herb is the only one I know of that is reportedly better when dried. I will hang on to my trusty old oregano that has thrived in my hot, alkaline soil for years, it is beautiful in and out of bloom. I have been too lazy to dry it, but a big handful picked fresh is always welcome in my kitchen.

Mint is often the subject of complaints since it is very enthusiastic. it will cover ground fast and its tight roots will compete successfully with any ot her plant in its path. But the weedeater keeps mine in bounds and I would never want to face a hot summer without it for my iced tea, lemonade and mint juleps. Or face winter without mint jelly. It is also famous for its health benefits, helping with good digestion, weight loss, relief from nausea, depression, fatigue, headaches, asthma, memory loss, and skin care.

her plant in its path. But the weedeater keeps mine in bounds and I would never want to face a hot summer without it for my iced tea, lemonade and mint juleps. Or face winter without mint jelly. It is also famous for its health benefits, helping with good digestion, weight loss, relief from nausea, depression, fatigue, headaches, asthma, memory loss, and skin care.

Rosemary has just as impressive a list of health claims; it is said to be good for us: boosting memory, improving our moods, reducing inflammation, relieving pain, protecting our immune systems, preventing premature aging. I grow it because it tastes good, looks good and smells divine. The Egyptians, Romans and Greeks considered the herb to be sacred. And the name? The Virgin Mary is said to have spread her blue cloak over a rosemary bush with white flowers and rested there. The flowers turned the familiar beautiful blue and the herb became known as “Rose of Mary.”

Living without herbs? Unpossible.

The producers of herbicides and pesticides do not care. Milkweed, the only plant the monarch caterpillar eats, is being wiped out by herbicide spraying–mostly to achieve the mass production of corn and soybeans. The death of the caterpillars is the result of the killing of the milkweed by herbicides and also because of the heavy use of insecticides, toxic to them and to the adult butterflies. Wouldn’t it be great if it were a status symbol to have milkweed all over your lawn? Lawn owners don’t think so.

The producers of herbicides and pesticides do not care. Milkweed, the only plant the monarch caterpillar eats, is being wiped out by herbicide spraying–mostly to achieve the mass production of corn and soybeans. The death of the caterpillars is the result of the killing of the milkweed by herbicides and also because of the heavy use of insecticides, toxic to them and to the adult butterflies. Wouldn’t it be great if it were a status symbol to have milkweed all over your lawn? Lawn owners don’t think so.

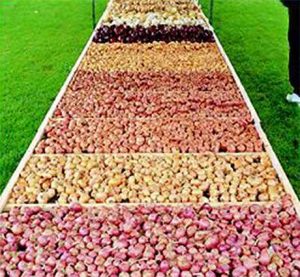

use the sets available in nurseries and grocery stores. However, they grow easily from seed: in fact, if you want green onions in the garden, you have to plant from seed since the sets are only ‘big’ onions as far as I know. Green onions are the favorite onion in China, where onions have been enthusiastically written about for over 5000 years.

use the sets available in nurseries and grocery stores. However, they grow easily from seed: in fact, if you want green onions in the garden, you have to plant from seed since the sets are only ‘big’ onions as far as I know. Green onions are the favorite onion in China, where onions have been enthusiastically written about for over 5000 years. the curative powers of the onion appear in the great medical book, Charaka – Sanhita. The Egyptians believed the onion to symbolize eternity with its circles within circles and buried it with the dead. Greeks ate many pounds of onions and rubbed onions all over their bodies before athletic competitions, including the early Olympics.

the curative powers of the onion appear in the great medical book, Charaka – Sanhita. The Egyptians believed the onion to symbolize eternity with its circles within circles and buried it with the dead. Greeks ate many pounds of onions and rubbed onions all over their bodies before athletic competitions, including the early Olympics.  st years. They come up in the potting soil like little green hair. In the garden, even when very small, they survive well since pests like bugs and rabbits do not eat them. Leek gardeners advise putting the leeks in a trench and gradually filling it as the leeks grow to produce the long white root. I am too lazy for all that and just plant them. They are lovely in the kitchen, Julia Child is a master of their use, for example her

st years. They come up in the potting soil like little green hair. In the garden, even when very small, they survive well since pests like bugs and rabbits do not eat them. Leek gardeners advise putting the leeks in a trench and gradually filling it as the leeks grow to produce the long white root. I am too lazy for all that and just plant them. They are lovely in the kitchen, Julia Child is a master of their use, for example her

ith the hoe. It had popped up all over the garden for years, a tropical plant that loves hot summer days and hates the cold. It is native to Africa and Southeast Asia but is grown and used by cooks all over the world. Of course such a well-traveled plant has many names, basil being derived from Latin meaning kingly plant. It is like a king in the kitchen with it strong taste and scent; my son makes pesto each year, I love it raw or cooked, in salads, on bruschetta, any way at all. And there are dozens of kinds of basil: sweet basil, cinnamon basil, purple basil, anise or Persian basil, all worth growing.

ith the hoe. It had popped up all over the garden for years, a tropical plant that loves hot summer days and hates the cold. It is native to Africa and Southeast Asia but is grown and used by cooks all over the world. Of course such a well-traveled plant has many names, basil being derived from Latin meaning kingly plant. It is like a king in the kitchen with it strong taste and scent; my son makes pesto each year, I love it raw or cooked, in salads, on bruschetta, any way at all. And there are dozens of kinds of basil: sweet basil, cinnamon basil, purple basil, anise or Persian basil, all worth growing. ge plant in the middle of the path last year. This year it is thriving at the feet of a grapevine. When temperatures dropped to 13 degrees in the winter I put a bucket over the plant and it was unharmed. Its leaves are very welcome in the kitchen during the cold weather. Parsley doesn’t mind hot summer weather either. I have found it to be delicious in salsa. The combination of tomatoes, onion, peppers and cilantro is grand; but cilantro likes it cool and is often gone by the time the tomatoes and peppers are ripe.

ge plant in the middle of the path last year. This year it is thriving at the feet of a grapevine. When temperatures dropped to 13 degrees in the winter I put a bucket over the plant and it was unharmed. Its leaves are very welcome in the kitchen during the cold weather. Parsley doesn’t mind hot summer weather either. I have found it to be delicious in salsa. The combination of tomatoes, onion, peppers and cilantro is grand; but cilantro likes it cool and is often gone by the time the tomatoes and peppers are ripe. A friend whose thyme had spread too much brought me a beautiful clump several weeks ago and it is doing well. I would like this plant to cover as much of the garden as it likes, to go out of control. This herb also has a venerable past: it was used for embalming by the Egyptians, as incense by the the Greeks, used to flavor cheese by the Romans and used to cover bad smells by medieval Europeans. It’s loaded with health benefits. Bees love its flowers. Fungus doesn’t like it; bugs don’t bother it. Did I say I love this plant?

A friend whose thyme had spread too much brought me a beautiful clump several weeks ago and it is doing well. I would like this plant to cover as much of the garden as it likes, to go out of control. This herb also has a venerable past: it was used for embalming by the Egyptians, as incense by the the Greeks, used to flavor cheese by the Romans and used to cover bad smells by medieval Europeans. It’s loaded with health benefits. Bees love its flowers. Fungus doesn’t like it; bugs don’t bother it. Did I say I love this plant? It grows into a large clump and its flowers are beautiful. High-end chefs use the flowers in their expensive dishes. It is reportedly hard to get an oregano plant that has ‘real’ oregano flavor. I may order Greek oregano and Syrian oregano this year from a reliable herb nursery. I understand that really strong oregano can numb the tongue. And the herb is the only one I know of that is reportedly better when dried. I will hang on to my trusty old oregano that has thrived in my hot, alkaline soil for years, it is beautiful in and out of bloom. I have been too lazy to dry it, but a big handful picked fresh is always welcome in my kitchen.

It grows into a large clump and its flowers are beautiful. High-end chefs use the flowers in their expensive dishes. It is reportedly hard to get an oregano plant that has ‘real’ oregano flavor. I may order Greek oregano and Syrian oregano this year from a reliable herb nursery. I understand that really strong oregano can numb the tongue. And the herb is the only one I know of that is reportedly better when dried. I will hang on to my trusty old oregano that has thrived in my hot, alkaline soil for years, it is beautiful in and out of bloom. I have been too lazy to dry it, but a big handful picked fresh is always welcome in my kitchen. her plant in its path. But the weedeater keeps mine in bounds and I would never want to face a hot summer without it for my iced tea, lemonade and mint juleps. Or face winter without mint jelly. It is also famous for its health benefits, helping with good digestion, weight loss, relief from nausea, depression, fatigue, headaches, asthma, memory loss, and skin care.

her plant in its path. But the weedeater keeps mine in bounds and I would never want to face a hot summer without it for my iced tea, lemonade and mint juleps. Or face winter without mint jelly. It is also famous for its health benefits, helping with good digestion, weight loss, relief from nausea, depression, fatigue, headaches, asthma, memory loss, and skin care.

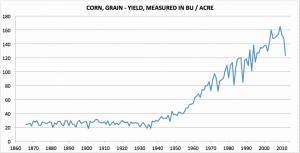

I am a little grumpy about all this corn since I planted eight hills of it and have two plants up–both about ankle high. I put in a hybrid, bought at the grocery store, that I imagine has been bred to require lots of commercial fertilizer. Modern corn varieties absolutely love petroleum-based commercial fertilizers. Production skyrocketed after WWII. In 1947 the huge munitions plant at Muscle Shoals, Alabama, stopped making explosives and finding themselves with lots of leftover ammonium nitrate, started making chemical fertilizer. The world quickly followed.

I am a little grumpy about all this corn since I planted eight hills of it and have two plants up–both about ankle high. I put in a hybrid, bought at the grocery store, that I imagine has been bred to require lots of commercial fertilizer. Modern corn varieties absolutely love petroleum-based commercial fertilizers. Production skyrocketed after WWII. In 1947 the huge munitions plant at Muscle Shoals, Alabama, stopped making explosives and finding themselves with lots of leftover ammonium nitrate, started making chemical fertilizer. The world quickly followed.

Herbivores evolved to eat grass; corn gives them stomach pain which requires antibiotics to keep the poor souls living until slaughter. Not that I am advocating any form of vegetarianism; that requires plowing up river banks, cutting down forests, transforming prairies — at the cost of destroying biodiversity (wild plants, animals and insects). Biodiversity has declined by more than a quarter in the last 35 years; perhaps over 50% since 1970. http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/biodiversity/threatsto_biodiversity/. In part this destruction is to provide the seeds, nuts, oils and soy for a non-animal diet. Poor corn; it’s not the only problem.

Herbivores evolved to eat grass; corn gives them stomach pain which requires antibiotics to keep the poor souls living until slaughter. Not that I am advocating any form of vegetarianism; that requires plowing up river banks, cutting down forests, transforming prairies — at the cost of destroying biodiversity (wild plants, animals and insects). Biodiversity has declined by more than a quarter in the last 35 years; perhaps over 50% since 1970. http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/biodiversity/threatsto_biodiversity/. In part this destruction is to provide the seeds, nuts, oils and soy for a non-animal diet. Poor corn; it’s not the only problem.

Plantswoman is on a little vacation, returning 4/11/18. This post is republished from 3/22/2017

Plantswoman is on a little vacation, returning 4/11/18. This post is republished from 3/22/2017

Nurseries, grocery stores and hardware stores are packed right now with annuals for sale. No pre-planning, no winter wait necessary. The annual plants I like best for bees include

Nurseries, grocery stores and hardware stores are packed right now with annuals for sale. No pre-planning, no winter wait necessary. The annual plants I like best for bees include

y garden is the native, Passion Vine. Its flowers are drop dead beautiful and appear to have come from 1970’s movie about an alien invasion. I ordered the vine from an acclaimed nursery that specializes in native plants, I purchased another from a highly rated local nursery and I have planted it from seed. All dead–even though native plants are supposed to grow well here. I put in my fourth try yesterday; from the Home Depot. What the heck.

y garden is the native, Passion Vine. Its flowers are drop dead beautiful and appear to have come from 1970’s movie about an alien invasion. I ordered the vine from an acclaimed nursery that specializes in native plants, I purchased another from a highly rated local nursery and I have planted it from seed. All dead–even though native plants are supposed to grow well here. I put in my fourth try yesterday; from the Home Depot. What the heck. Nevertheless, when a neighbor offered a clump of daylilies after her spring cleanup, I drove right over to get them. I pulled the big clump apart and wound up with twenty or so starts of the Daylily, Stella D’Oro. I have put my new daylilies in the vegetable garden where the chickens are not permitted to go; I am hoping the plants will thrive and that my intelligent and resourceful birds will not find another feast. Hope.

Nevertheless, when a neighbor offered a clump of daylilies after her spring cleanup, I drove right over to get them. I pulled the big clump apart and wound up with twenty or so starts of the Daylily, Stella D’Oro. I have put my new daylilies in the vegetable garden where the chickens are not permitted to go; I am hoping the plants will thrive and that my intelligent and resourceful birds will not find another feast. Hope.

e a happy place, just the thing to make a woman longing for home make peace with a new world.

e a happy place, just the thing to make a woman longing for home make peace with a new world. India after they fell in love with the Palash trees, covered with red flowers, and other exotics. They became devoted to the brightly colored lotuses that grew wild because of the abundant water that flowed from the Himalayas. Southern India? A dozen famous names occur throughout our literature; for example, Shalimar, a household word–stunning with trees and water features. The grand garden alley here makes it clear that the single-mindedness, the madness to create perfection apparently extended through many generations in India.

India after they fell in love with the Palash trees, covered with red flowers, and other exotics. They became devoted to the brightly colored lotuses that grew wild because of the abundant water that flowed from the Himalayas. Southern India? A dozen famous names occur throughout our literature; for example, Shalimar, a household word–stunning with trees and water features. The grand garden alley here makes it clear that the single-mindedness, the madness to create perfection apparently extended through many generations in India. In the spring of 74 AD, that book tells the story of the Emperor putting carp into a pond and rejoicing; the animation of fish are now always a part of a Japanese garden. Not long after, another Emperor expanded the idea to a lake where he could take his favorite concubine to feast and bask in the beauty of the combination of water and plants. I have never toured a Japanese garden that did not contain a water feature.

In the spring of 74 AD, that book tells the story of the Emperor putting carp into a pond and rejoicing; the animation of fish are now always a part of a Japanese garden. Not long after, another Emperor expanded the idea to a lake where he could take his favorite concubine to feast and bask in the beauty of the combination of water and plants. I have never toured a Japanese garden that did not contain a water feature.