I attended a beautiful performance of music this week in a church built in the 1850’s after the flood of Anglican immigrants into Texas. Loaded with architectural features, perhaps too many, I picture the enthusiastic new settlers, determined to improve on the old Spanish Mission Churches. But the old mission churches have a kind of grace that cannot be topped by enthusiasm and wealth. The Spanish monks had come here to improve Native Americans when Spain was conducting its religious Inquisition. Imagine. The desire to improve leads us all down difficult paths.

What would the Chinese gardeners who improved the beautiful Wisteria sinensis hundreds of years ago think if they learned this grand plant is now banned in many American states. It is listed as an invasive, swallowing trees and clogging waterways throughout the American South. http://www.texasinvasives.org/plant_database/detail.php?symbol=WISI

I dutifully planted Wisteria frutescens, (pictured above). It is a pretty lavender color with 6-inch racemes and no scent. But the Chinese plant is the most vivid purple or blue with racemes at least 12-inches long. It grows lushly and smells heavenly. I long for one, but resist.

I like improvements. I bought an ‘improved’ Kieffer pear tree two years ago. Pear trees, especially the Kieffers, used to be rock solid, a touch of disease maybe here and there, but entirely reliable. My grandparents had two huge trees with fruit crowding the branches.  Then fire blight moved in and pear trees were devastated. I have tried pruning off the blackened branches that occur when the bacteria strikes and aggressively used the strongest organic sprays I could find. I even poured bleach around an infected tree as instructed. What I do now when I see a blackened branch is spray with Neem Oil up to half a dozen times during the season. Neem Oil is pressed from the fruit and seeds of the Neem plant, native to the Indian subcontinent. It is one of my favorite organic controls. My Kieffers, the improved and unimproved are able to recover with this gentle assistance. Both trees are equally beautiful so I am waiting to see the difference–cheering for the little improved tree to pull ahead since, I am, after all, a modern woman.

Then fire blight moved in and pear trees were devastated. I have tried pruning off the blackened branches that occur when the bacteria strikes and aggressively used the strongest organic sprays I could find. I even poured bleach around an infected tree as instructed. What I do now when I see a blackened branch is spray with Neem Oil up to half a dozen times during the season. Neem Oil is pressed from the fruit and seeds of the Neem plant, native to the Indian subcontinent. It is one of my favorite organic controls. My Kieffers, the improved and unimproved are able to recover with this gentle assistance. Both trees are equally beautiful so I am waiting to see the difference–cheering for the little improved tree to pull ahead since, I am, after all, a modern woman.

Modern or not, my head spins when I read seed catalogues and I ordered a corn seed hybrid last year called “Gotta Have It” from Gurney’s. You would think the name would have been a warning. Gurney’s treats its corn seeds and promises a half dozen improvements. The seeds arrived and looked like pieces of the ‘fiery’ Cheetos for sale in gas stations. Since the catalogue did not give specifics, I called the nursery to make sure these seeds would not hurt my bees or earthworms. Given some sketchy, if reassuring answers, I planted the things and they did not do any better than the old fashioned varieties like “Silver Queen.” The corn story is a future post; its greedy nature, the chemicals used in its production– and corn costs about 30% more to grow than its sale price. I admit to having issues with growing corn at all; I only have room for about a dozen plants and they need more hand germination than I have provided in the past so I get ears full of kernels. But the plants are beautiful in the garden and my cow and sheep consider a freshly pulled cornstalk the equivalent of dinner in Paris.

es appear in almost every pot. Without thinning, The Tragedy of the Commons would occur in my little 4-inch plastic pots, each tiny seedling acting as an individual, using as many nutrients as possible for its own benefit. Without thinning: sickly, stunted plants emerge. So I discard the extras since I have no room for them. The little dying Broccoli bodies pictured here bother me, make me sad, break my heart.

es appear in almost every pot. Without thinning, The Tragedy of the Commons would occur in my little 4-inch plastic pots, each tiny seedling acting as an individual, using as many nutrients as possible for its own benefit. Without thinning: sickly, stunted plants emerge. So I discard the extras since I have no room for them. The little dying Broccoli bodies pictured here bother me, make me sad, break my heart.

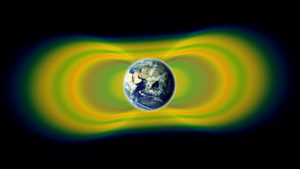

tic field that extends from Earth’s interior into Space. This field protects us from the solar winds, cosmic rays, ultraviolet radiation and certain destruction. Beyond are the Van Allen radiation belts, pictured to the right– “giant swaths of magnetically trapped, highly energetic charged particles that surround Earth.” Getting through these belts is a big problem for NASA. http://www.space.com/33948-van-allen-radiation-belts.html.

tic field that extends from Earth’s interior into Space. This field protects us from the solar winds, cosmic rays, ultraviolet radiation and certain destruction. Beyond are the Van Allen radiation belts, pictured to the right– “giant swaths of magnetically trapped, highly energetic charged particles that surround Earth.” Getting through these belts is a big problem for NASA. http://www.space.com/33948-van-allen-radiation-belts.html.

is of a levee made of sausage-shaped baskets of woven bamboo filled with stones held in place by wooden tripods.

is of a levee made of sausage-shaped baskets of woven bamboo filled with stones held in place by wooden tripods.

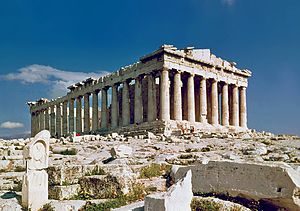

But with civilization, the land on the Greek peninsula and surrounding islands was spoiled; the extensive old Greek forests felled, large fertile grasslands degraded.

But with civilization, the land on the Greek peninsula and surrounding islands was spoiled; the extensive old Greek forests felled, large fertile grasslands degraded.