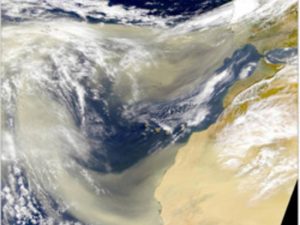

A huge plume of dust rose up out of the Sahara Desert last week and traveled 5000 miles, across the Atlantic, up through parts of Mexico and the American South. The dust hit the Texas Gulf Coast and spread throughout the State. The red African dust has been hanging over my little farm this past week. While the current dusty red atmosphere is new to me, violent wind storms in the Sahara are common. Every year 182 million tons of dust are blown into the upper atmosphere and driven by the trade winds to the Americas. 182 million tons.

The dust, called mineral dust, is loaded with nutrients: primarily iron and phosphorus. When this airborne fertilizer falls into the ocean, it creates a pr oblem endemic to all fertilizers: rampant growth of the wrong thing. A “red tide” of algae growth poisons huge numbers of fish and other marine life. Scientists also believe the microbes in the dust may be poisoning coral contributing to death of coral reefs.

oblem endemic to all fertilizers: rampant growth of the wrong thing. A “red tide” of algae growth poisons huge numbers of fish and other marine life. Scientists also believe the microbes in the dust may be poisoning coral contributing to death of coral reefs.

Naturally humans worry about the presence of foreign red dust. It may bring fungus, bacteria and harmful chemical residues. It certainly causes sinus and respiratory issues. And red dust, well, it makes things a dirty, dusty red. Because of the iron.

But it turns out that all these complaints about the red mineral dust do not weigh very heavily since, on the other side of the scale, is its contribution to the generation of oxygen.

Every breath we take is a gift from plants. Rain forests are well known to be the ‘lungs’ of the Earth, burning carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen. The African mineral dust often settles on the Amazon rain forest that gratefully soaks up the iron, phosphorus and other nutrients provided by Mother Africa. The Saharan dust is largely responsible for the fertility of the rain forests.

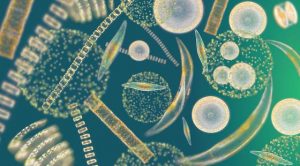

This mineral dust also feeds the world’s oceans. Tiny ocean plants called Phytoplankton use photosynthesis to live, a process that uses sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into carbohydrates and oxygen.  The little plants, most of which are invisible to the naked eye, create about half of the oxygen we breathe. Nutrients like the iron and phosphorus in the African mineral dust are in short supply in marine ecosystems. Without the fertilizer from the Sahara, the health of phytoplankton and the oceans would decline significantly. link

The little plants, most of which are invisible to the naked eye, create about half of the oxygen we breathe. Nutrients like the iron and phosphorus in the African mineral dust are in short supply in marine ecosystems. Without the fertilizer from the Sahara, the health of phytoplankton and the oceans would decline significantly. link

I was struggling with my own iron issues when the story of the red mineral dust cloud appeared in the new s. I have a persimmon tree that cannot seem to absorb iron so its leaves are a creepy pale green color. I’m treating the problem with a special easy- to- absorb iron called chelated. I hope it works since, if the tree cannot get iron it will die. The iron allows access to crucial enzymes and pigments and is necessary for the tree’s energy production. Which translates into no persimmon sherbet for me. I like the idea that my tree shares a need with the microscopic phytoplankton plants in the ocean.

s. I have a persimmon tree that cannot seem to absorb iron so its leaves are a creepy pale green color. I’m treating the problem with a special easy- to- absorb iron called chelated. I hope it works since, if the tree cannot get iron it will die. The iron allows access to crucial enzymes and pigments and is necessary for the tree’s energy production. Which translates into no persimmon sherbet for me. I like the idea that my tree shares a need with the microscopic phytoplankton plants in the ocean.

Of course the necessity of phosphorus, delivered by the Saharan dust, is well known. It is in every bag of fertilizer we buy. It drives the conversion of key biochemical reactions in plants and is a vital part of DNA, our memory unit and the memory unit of plants as well. Phosphorus is a big player in the capture and conversion of the sun’s energy: our old friend, photosynthesis.

So here we have a potential villain. It sweeps across the world killing fish and coral. It makes us sick and dirties our air. But it does the work of a hero by feeding the phytoplankton and the rain forest so we have plenty of oxygen. The red African dust is quite the character. Not one on a human scale as seen on the the stage or a movie screen, but one that comes out of a desert that covers about three and a half million square miles, that measures in tons and travels thousands of miles. It engages with the most crucial building blocks of nature. The red dust exists on a truly grand scale, the scale of a planet.