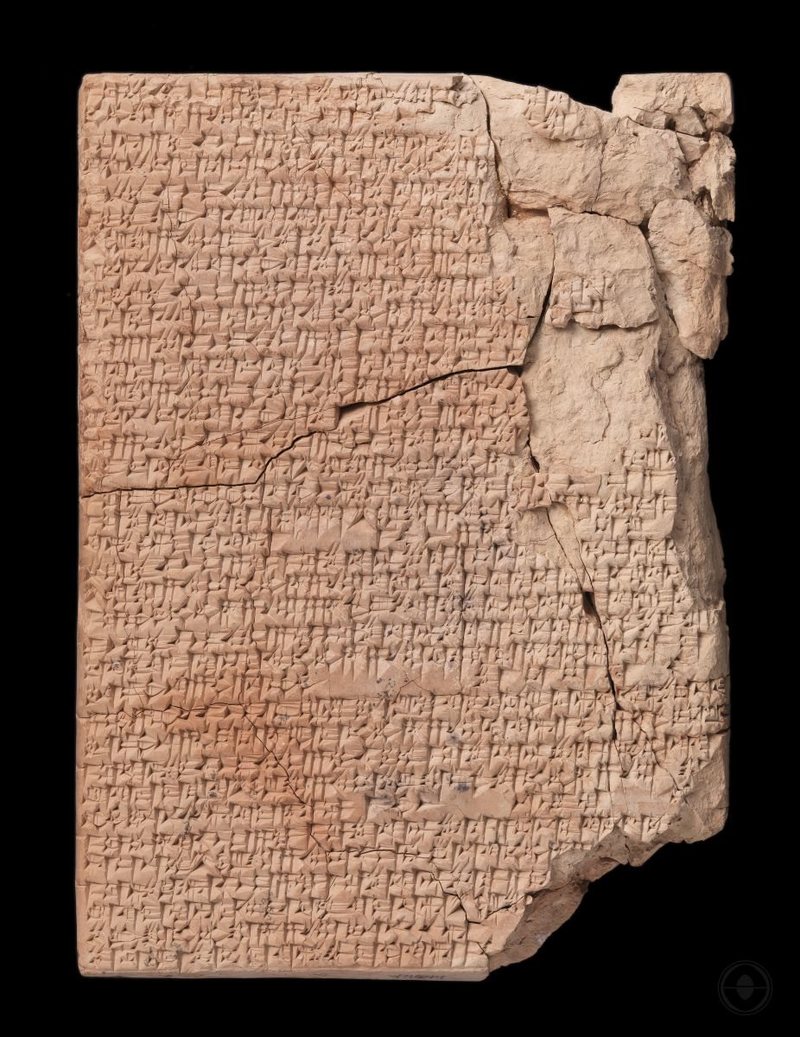

I put up over two gallons of honey last week. Much of it was purchased by friends and I set aside some for holiday gifts. But a few jars are for me to enjoy. Harvesting and eating honey is a way for me to connect with my Neolithic farming ancestors — who are charged by historians with the exploitation of bees –just as we are today. The ancient hollow log pictured above shows an example of the comb treasured by Sto ne Age raiders of hives 8500 years ago in France. link

ne Age raiders of hives 8500 years ago in France. link

I wonder if my Stone Age counterpart got honey all over the place as I did when I extracted and bottled my honey last week. I did not use the big circular extractor in my garage, but just scraped off the wax caps on the hive frames and let the honey drain all night Then I strained it through a fairly large mesh to preserve all the precious pollen and nutrients. The friend who gave me the extractor, when he divested himself of his bees and bee equipment, also gave me a box of eight ounce plastic squeeze bottles. I used these bottles only after I ran out of my supply of pretty decorative glass bottles. What would my Stone Age counterpart have thought about these little plastic bottles, considered mundane and practical by me; perhaps wondrous by her.  And since much of the honey for sale now has been heated and ultra filtered; I wonder how often my ancestors heated the honey to extract if faster and more thoroughly; I wonder if they filtered it at all.

And since much of the honey for sale now has been heated and ultra filtered; I wonder how often my ancestors heated the honey to extract if faster and more thoroughly; I wonder if they filtered it at all.

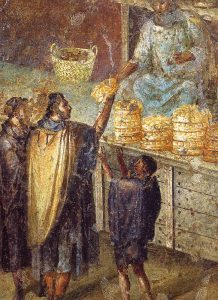

The grocery store shelves are now filled with jars of honey to which sugar and water have often been added to increase profits. Mass produced honey has been basically killed by the ‘pasteurization’ process; and, should any remaining nutrients survive, they are filtered out by high-tech machines. We are told that this ultra processing makes the honey smoother and more transparent. link

Vaughn Bryant, professor of anthropology at Texas A&M University, has spent decades analyzing commercial honey; he peers through his microscope at a sample, looking for pollen or other signs of life and says, “Nothing!” A modern day crusader, he has led opposition to the sale of dead honey in ‘big box’ stores; and, he has revealed honey contaminated by heavy metals and other toxins dumped in the United States by China, India and other countries. Casting a wide net, Dr. Bryant has extensively researched ancient honey discovered by archaeologists and geologists who have found honey in their research sites.

We have learned that honey doesn’t spoil because of its acidic and ant ibacterial content. Three-thousand year old honey found in an Egyptian tomb was found to be edible. link Honey was found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. Recognizable honey stains, 5500 years old, were found in ceramic vessels in ancient Georgia. The earliest apiary with more than 100 hives was found in Israel, dating to the 9th century B.C.E.– contemporaneous to King Solomon.

ibacterial content. Three-thousand year old honey found in an Egyptian tomb was found to be edible. link Honey was found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. Recognizable honey stains, 5500 years old, were found in ceramic vessels in ancient Georgia. The earliest apiary with more than 100 hives was found in Israel, dating to the 9th century B.C.E.– contemporaneous to King Solomon.

So why do we kill it? Honey has been beloved by humans for thousands of years and used to honor the dead, satisfy our love of sweets; and importantly, to improve our health. link

The health benefits of raw honey are well known. Unheated honey, filtered only enough to remove wax and dead bees has dozens of amino acids and is loaded with minerals and vitamins. It also contains almost 30 kinds of bioactive plant compounds that act as antioxidants. All of which contribute to honey’s reputation for reducing inflammation, lowering the risk of heart disease, fighting cancer, helping to control blood sugar by improving liver function, improving vascular function, assisting with weight management, suppressing coughs, boosting immunity, healing wounds and helping to lower cholesterol. link.

Why DO we kill it.

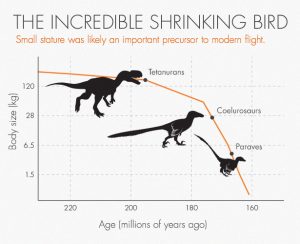

The Sussex are touted by chicken sellers as the bird with ‘everything.’ Her antecedents are said to have been living in England when the Romans invaded in 43 BC. The modern Sussex are family birds– friendly, easy-going and intelligent. My little Sussex seems to the the leader of the three new girls. They are all sticking to the barn and the fenced coop right now, partly because of the heat and partly because a family of hawks live nearby in a large Oak and at least eight of them are on patrol almost all day.

The Sussex are touted by chicken sellers as the bird with ‘everything.’ Her antecedents are said to have been living in England when the Romans invaded in 43 BC. The modern Sussex are family birds– friendly, easy-going and intelligent. My little Sussex seems to the the leader of the three new girls. They are all sticking to the barn and the fenced coop right now, partly because of the heat and partly because a family of hawks live nearby in a large Oak and at least eight of them are on patrol almost all day. I also have a regal Jersey Giant chick who will grow to about 10 pounds, way too big for a hawk to lift off the ground. Bred in New Jersey late in the 19th century, these giants are supposed to be very sociable, especially friendly to children. You can see that the young farmer who supplied my new chicks likes companionable breeds. The Jersey Giants were on a critically endangered list in 2001 but now have been moved to a watch list. I always like to try and preserve these historic breeds.

I also have a regal Jersey Giant chick who will grow to about 10 pounds, way too big for a hawk to lift off the ground. Bred in New Jersey late in the 19th century, these giants are supposed to be very sociable, especially friendly to children. You can see that the young farmer who supplied my new chicks likes companionable breeds. The Jersey Giants were on a critically endangered list in 2001 but now have been moved to a watch list. I always like to try and preserve these historic breeds. Bred in Chile, these chickens have a puff of feathers around their heads that reveal the wide standards of what is beautiful in the chicken world.

Bred in Chile, these chickens have a puff of feathers around their heads that reveal the wide standards of what is beautiful in the chicken world.

Paintings and illustrations abound of the beautiful and very feminine Virgin Mary with the Crescent Moon.

Paintings and illustrations abound of the beautiful and very feminine Virgin Mary with the Crescent Moon. with the crescent moon, as is the Roman goddess of the hunt, Diana. I am sure intuition, empathy and patience help one to hunt successfully, but it is interesting that such a masculine modern pastime was viewed so differently in the ancient world.

with the crescent moon, as is the Roman goddess of the hunt, Diana. I am sure intuition, empathy and patience help one to hunt successfully, but it is interesting that such a masculine modern pastime was viewed so differently in the ancient world.

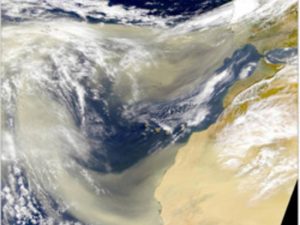

oblem endemic to all fertilizers: rampant growth of the wrong thing. A “red tide” of algae growth poisons huge numbers of fish and other marine life. Scientists also believe the microbes in the dust may be poisoning coral contributing to death of coral reefs.

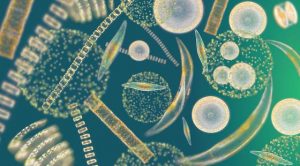

oblem endemic to all fertilizers: rampant growth of the wrong thing. A “red tide” of algae growth poisons huge numbers of fish and other marine life. Scientists also believe the microbes in the dust may be poisoning coral contributing to death of coral reefs. The little plants, most of which are invisible to the naked eye, create about half of the oxygen we breathe. Nutrients like the iron and phosphorus in the African mineral dust are in short supply in marine ecosystems. Without the fertilizer from the Sahara, the health of phytoplankton and the oceans would decline significantly.

The little plants, most of which are invisible to the naked eye, create about half of the oxygen we breathe. Nutrients like the iron and phosphorus in the African mineral dust are in short supply in marine ecosystems. Without the fertilizer from the Sahara, the health of phytoplankton and the oceans would decline significantly.  s. I have a persimmon tree that cannot seem to absorb iron so its leaves are a creepy pale green color. I’m treating the problem with a special easy- to- absorb iron called chelated. I hope it works since, if the tree cannot get iron it will die. The iron allows access to crucial enzymes and pigments and is necessary for the tree’s energy production. Which translates into no persimmon sherbet for me. I like the idea that my tree shares a need with the microscopic phytoplankton plants in the ocean.

s. I have a persimmon tree that cannot seem to absorb iron so its leaves are a creepy pale green color. I’m treating the problem with a special easy- to- absorb iron called chelated. I hope it works since, if the tree cannot get iron it will die. The iron allows access to crucial enzymes and pigments and is necessary for the tree’s energy production. Which translates into no persimmon sherbet for me. I like the idea that my tree shares a need with the microscopic phytoplankton plants in the ocean.

t killed by herbicides. The plan was for the herbicides to kill all plants in a field other than the genetically modified corn or soybeans. It is entertaining to me that weedy plants are developing their own genetic modifications to resist the poisons. Poor Big Ag farmers, they have to keep using more and more of old herbicides and are always on the lookout for “new” and usually more toxic herbicides so they can stay ahead of the plants.

t killed by herbicides. The plan was for the herbicides to kill all plants in a field other than the genetically modified corn or soybeans. It is entertaining to me that weedy plants are developing their own genetic modifications to resist the poisons. Poor Big Ag farmers, they have to keep using more and more of old herbicides and are always on the lookout for “new” and usually more toxic herbicides so they can stay ahead of the plants.

y do more than just provide the oxygen. Like any good set of lungs, trees filter pollutants and clean the air for us. A new study estimates that the Earth has three trillion trees. These trees are represented in the graphic to the left in the dark green bands. Another study estimates that 400 billion mature leafy trees exist and these big trees produce enough clean oxygen “… for the lifetime of ten people each season! There are 400 billion trees, 6.7 billion people on Earth — every person has 60 trees.”

y do more than just provide the oxygen. Like any good set of lungs, trees filter pollutants and clean the air for us. A new study estimates that the Earth has three trillion trees. These trees are represented in the graphic to the left in the dark green bands. Another study estimates that 400 billion mature leafy trees exist and these big trees produce enough clean oxygen “… for the lifetime of ten people each season! There are 400 billion trees, 6.7 billion people on Earth — every person has 60 trees.”

They cut every tree. The deforestation of the island led to decline, led to a few suvivors living a feral existence in caves eating rats and mice and possibly engaging in cannibalism.

They cut every tree. The deforestation of the island led to decline, led to a few suvivors living a feral existence in caves eating rats and mice and possibly engaging in cannibalism.